A Resurrection Worth Singing About, Even in the Storm

In the face of war, abuse, and sad throwing-up children, I believe in its happy ending

Happy Easter, a few days late—or Merry Christmas might be more appropriate, given the wintery weather we’ve had here in the Upper Midwest the past few weeks.

This newsletter is supposed to go out every Sunday, and I had hoped to get it out on Easter Sunday, but our travels and other events conspired against it; then I hoped to get it out a day late, but on Monday night as I was working on this essay I got a call from the leader of our refugee support group with news of a crisis with the two Afghan families we’ve been supporting since December. We spent a couple hours troubleshooting the situation, first on the phone and then by text. In the middle of all that, I got a call from a friend who has been recovering in a nursing home for months and months, alternately wailing and hyperventilating because she had been physically and mentally abused by a nurse over the weekend, triggering vivid flashbacks of the abuse she suffered as a kid. While I was talking her through that (and texting the Afghan refugee crisis), I could hear my youngest son out in the hallway wailing because he was about to throw up again, just as he has every day for the past five or six months due to his Crohn’s disease. “It’s not fair!” was his assessment of the situation; and boy, it sure isn’t.

Meanwhile, I see the Russians marked Easter by accelerating their slaughter of Ukrainians, which is one way to spend the holiday, I guess, if you don’t have anything better to do.

So. What about the Resurrection, then? What about Easter?

Let’s face it, the Resurrection was unbelievable even at the time; all four gospels record that the apostles’ first reaction to the news was disbelief. And why shouldn’t that be anyone’s first reaction? It’s a lot to swallow, this claim that the man Jesus, publicly tortured and executed by the Roman state, gave his grave the slip and now exists in some glorified state that transcends our usual experience of reality. It is hard to believe not only because it flies in the face of our normal experience of the natural world, but more importantly, because it seems too good to be true. Sure, we all want to believe in happily-ever-after endings, but those are the purview of children’s stories, right? As life’s many disappointments start piling up, we guard against more hurt by setting aside Disney’s fables in favor of, say, short stories from the pages of The New Yorker, where a “happy ending” might involve the protagonist sitting in his tenement apartment staring at cold pea soup as rainwater leaks from the ceiling onto his head, the happy ending being that at least now he’s liberated from any expectation of finding meaning in life.

And yet, on Saturday night my family still made our way out into the cold and snowy night to attend the Easter Vigil, and we still sang songs of the Resurrection. More amazingly, the New York Times reports that the Roman Catholic churches in Lviv were “packed” over the weekend, even as air-raid sirens mixed with the sound of church bells, and rockets continued to rain death from the east.

Are we crazy for celebrating Easter under these circumstances? Delusional? Anesthetizing the pain with the balm of ancient myth and ritual? Who, in this great age of technological wonderment, really believes that this man Jesus slipped through the certainties of our science to find a happy ending not only for himself, but for all creation?

Who can believe this, in the face of suffering, sadness, and breathtaking evil?

Well, we’re not crazy, and we’re not credulous. We sing our hopeful song even in the midst of the storm for good reason.

Before I mount my defense, though, let’s be clear about which resurrection we’re talking about here. The one I’m talking about isn’t the small resurrection of TV documentaries and magazine covers—one more event on the timeline of human history, too small to encompass what’s going on in Ukraine—too small even for the sadness of my throwing-up child.

This Resurrection that moves us to sing a hopeful song may have its roots in the cross that bore the man Jesus, but its branches touch all of us. God participates in the life and death of his creation not just in the instance one man, but through that one man, in every instance, everywhere: in Auschwitz and Rwanda and Ukraine, and in my throwing-up child, and in my friend wondering what she did to deserve being abused.

If the cross is planted in all these places, then so is the empty tomb, and the stone has been rolled away not only for Jesus, but for everyone; we only have to stand up and walk out into the morning light. This Resurrection opens the possibility of a happy ending for us all.

I would never expect anyone to believe this proposition blindly, especially not anyone on the receiving end of an evil intent on destroying them. Extraordinary claims do require extraordinary evidence. Yes, we rely on revelation for the initial proposition—we wouldn’t know about the empty tomb without the testimony of the Church. And we could not begin to believe without the gift of faith—that bone-deep divine friendship that moved Peter and John to run out to the empty tomb after receiving the report of the women. But reason, that sifter of experience and evidence, is the happy companion of faith, and no less necessary for sustaining belief. The disciples believed not only because the tomb was empty, but because they encountered the risen Christ in the flesh: they embraced his feet and touched his wounds, and he ate their food and blessed them with his breath.

It is the same for anyone who takes the Resurrection seriously. We begin to believe because we have encountered the risen Christ in one form or another, and our belief becomes a thing we can rely on as we test its implications day by day—daring to live, and daring to love, which are nearly the same thing, and not a little risky, either. I have encountered the cross a few more times than I’d like in my life; thankfully, now and then I’ve also realized with a sudden start that the risen Christ is standing right there in front of me. A handful of those encounters are enough to light your way through a whole lot of darkness.

The Resurrection opens the way for us to enter that darkness, bringing the light with us. We do this first by standing vigil at the foot of the cross, just as the women once stood vigil by the cross of Jesus. This is why we have crucifixes in our churches; but we should adopt this reverent posture not only in our churches and prayer corners, but wherever in the world we find the cross planted. We stand witness to the suffering of others for the simple reason that, by sharing their burden sympathetically, the gift of our presence might be a comfort, and maybe a sacrament of God’s presence, too. This might be why our weekly vigils for Ukraine feel less like political action and more like a form of prayer.

When we can, we enter the darkness by carrying the cross of those who suffer, just as Simon did for Jesus. We do what we can to ease their suffering directly by investing our time and resources, even to the point of sacrifice.

And if the forces of evil come out to fight, we go out to meet them on whatever battlefield we can find, and we fight. We fight back with a fierceness to match the enemy’s, but instead of wielding ICBMs and tanks and rockets, we wield the twin weapons of truth and love, always leading with love.

Don’t think I’m being allegorical: the nurse who abused my friend, the Russians who level one hospital after another, the Taliban who shut girls out of school—these evils need to be met with something more than pious words and symbolic protests.

I can’t go to Afghanistan or Ukraine. (If I did, I would be more hinderance than help, half-blind as I am.) But if the Taliban deny girls education in Afghanistan, I can help sponsor Afghan refugees here in Winona, enrolling their girls in school and cheering their every accomplishment. If I find my friend abused by a caretaker, I can stay on the phone to comfort her, then call whoever needs to know so the abuse can be stopped and remedied. If the Russians commit genocide in Ukraine and brandish nuclear weapons at the rest of the world, I can do what I can to urge boycotts and other nonviolent political action; and if that seems not enough by itself, I can “wage love” in other ways and other venues as fiercely as they wage war. In Christ, the power of love is fungible.

That leaves me with my sick, sad child languishing on the couch wishing he could be at school with his friends. No matter what I do to comfort or help him, at the end of the day, it isn’t going to be enough to make it better. The best I can do is to give him the gift of my sympathetic presence, and pray.

It is a reminder that the Resurrection—the one worth singing about, even in the storm—is not something we can bring about ourselves, but a gift, an extravagance freely given by the One who began the story in the first place, and who will guide us all to its happy ending.

Due to the lateness and length of this newsletter, the other usual features have the week off.

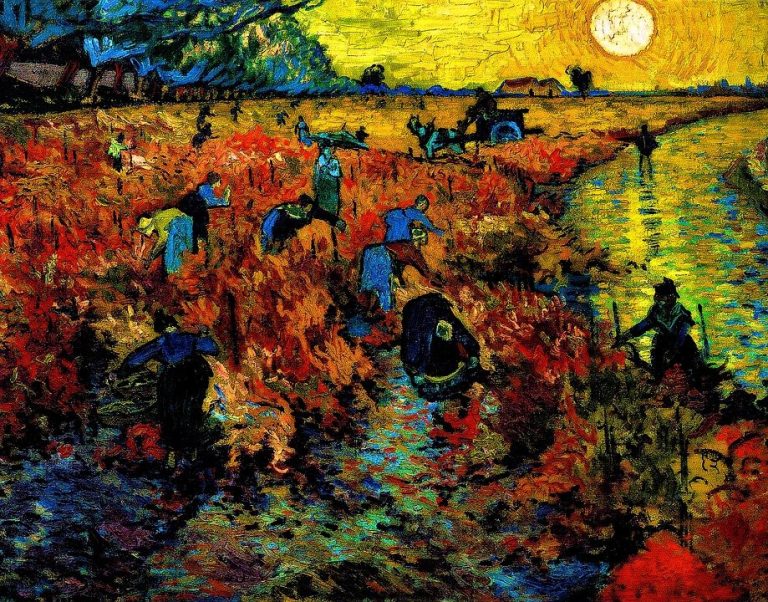

Image credit: Petar Milošević via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 3.0,