Into the Desert Once Again

If I’d been an Israelite at the time of the Exodus, I’m sure I would have been one of the cranky gripers and complainers; I know this because I don’t look forward to the season of Lent. Not at all. I like my sugar, caffeine, meat, chocolate, etc., etc. I get especially whiny on those fasting days; gimme my fleshpots, man—I’m done starving out here in the wilderness. Every Ash Wednesday, I can’t help thinking: If it’s February in Minnesota, isn’t Lent redundant?

I’m happy to pass through the sea on dry land any day of the week…but this long journey through the desert? On balance, I’d rather stay home.

I’d rather stay home . . . except that I’m in Egypt, and Egypt isn’t home. Yes, there might be couches and cushions and kettles of meat and breadsticks and beer, not to mention some amazing public architecture. It’s all good—except that someone has to pay for all this luxury, and that someone is me; and the price is my freedom…not my political freedom or even my personal autonomy, but my freedom to do good.

That’s what Moses and the Israelites were after, too. God instructs Moses to “go to the king of Egypt and say to him: The Lord, the God of the Hebrews, has come to meet us. So now, let us go a three days’ journey in the wilderness to offer sacrifice to the Lord, our God” (Exodus 3:18). The Lord has come to meet us; let us go worship him. That’s what was at stake for Moses and the Israelites: the ability to meet God with worship, celebration, and sacrifice. All Pharaoh had to do was give them the week off.

Now, I live on the banks of the Mississippi River, which is a long way from the banks of the Nile, but I am still in “Egypt” as long as there’s anything that prevents me from offering sacrifice to the Lord, my God—the one who has come to meet me. For the Israelites, it was Pharaoh who kept them from God. I’m not politically oppressed or legally enslaved, but that doesn’t mean I’m entirely free from the paradigm of enslavement. Like many in the wealthy West, my shackles and chains come in the form of comfort, security, and control. These things aren’t bad in themselves, of course, but neither are they good as an end in themselves. They’re good only insofar as they enable me to be good. They cannot be “pharaoh” or “king.” They cannot rule my life.

And that’s why I go into the desert . . . not for the sand in my shoes, the sunburn and sweat, but to be liberated from the forces that enslave me, and to learn how to be free . . . free to be good, even when being good requires sacrificing my own comfort, security, or control.

What am I talking about? I’m thinking particularly of my bed, which I find that I prefer early on a cold winter morning when it’s time to get up and let the dog out and wake the child for school. Or I think about the interruptions that break up my workday; I have my agenda set out, you know; I have my finish line. Now, an uninterrupted workday is a wonderful thing; but sometimes, those interruptions are “God’s agenda.” To be free under these conditions means not being a slave to my own agenda.

Personal security is usually good, too; but not if physical or financial security becomes my ultimate concern, trumping the virtues of charity and generosity. Prudence is often invoked to excuse parsimony. But short-sighted prudence isn’t a virtue. Prudence is only virtuous when its goal is the ultimate good. How many of us (and I include myself here) are like the rich man who built bigger barns (Luke 12:16-21) to store the surplus of his harvest? We may not have big barns, but we slave our lives away to save enough money for retirement. The ironic, if unspoken, implication is that we can’t rely on our friends, neighbors, and family to provide our basic care in our old age.

Is this real security? Or is the security of the inmate locked away for his own protection?

Freedom is about possibility. The wider your range of possibilities, the freer you are. “For God, all things are possible” (Matthew 19:26). The desert is a spiritual training ground for people who want this expansive freedom. It’s a necessary passage; there’s no stepping out of Egypt and right into the Promised Land, because real liberation requires a change not only in my external circumstances, but my heart, too: I have to unlearn the ways of slavery and learn the ways of freedom. If I don’t make this journey through the desert, I’ll just bring my slavey ways to wherever I end up, trading one master for another.

If all of this is true—if I want to leave Egypt—then why do I grumble and whine my way through Lent (mostly to myself, but sometimes out loud)? It’s only human nature, I suppose, to resist the hard work of growth and change.

The Israelites were great grumblers out there in the desert, of course: “Here in the wilderness the whole Israelite community grumbled against Moses and Aaron” (Exodus 16:2); “So the people complained against God and Moses, ‘Why have you brought us up from Egypt to die in the wilderness, where there is no food or water?’” (Numbers 21:5). That’s just two examples of many. The back-and-forth between God and the Israelites is the central conflict in the story of the Exodus. It boils down to this: the Israelites want to return to Egypt—they want to continue in their slavey ways.

I find God’s response to their complaining instructive for my own desert journey: “I will rain down bread from heaven for you” (Exodus 16:4).

If we’re going to make it from Egypt to the Promised Land, the only way that’s going to happen is with God’s help. And the good news is, God does not send us into the desert alone: he goes with us, supplying us with what we need—just enough, and no more. (Remember that he supplied the Israelites with enough manna every morning to last the day.) Just enough, so that we might learn the lessons of our liberation; just enough, so that we won’t be slaves to our whims and wants anymore.

Just enough, so that we might live in the expansive freedom of the Promised Land.

I am not entirely sure what I’m giving up for Lent this year. Given the tenor of this article, you’d think I’d enthusiastically embrace bread and water for the next forty days. Ain’t gonna happen. But whatever I give up may be less important than the attitude I bring into the desert. Will I go through Lent begrudgingly, or joyfully? Maybe this is why fasting isn’t the only recommended Lenten practice: we’re supposed to redouble our prayer and charity, too. Maybe this “trinity” of Lenten practices is meant to work together. I’ll report my findings on the other side.

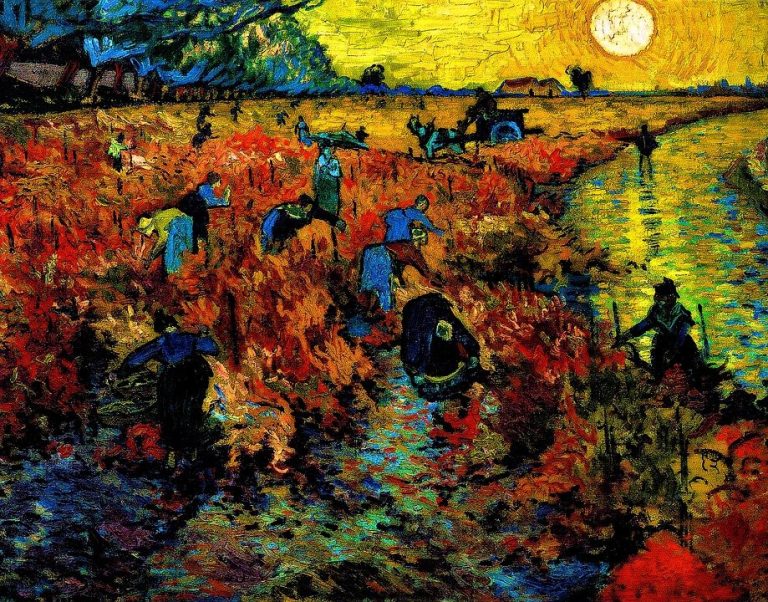

Photo credit: Marion from Pixabay